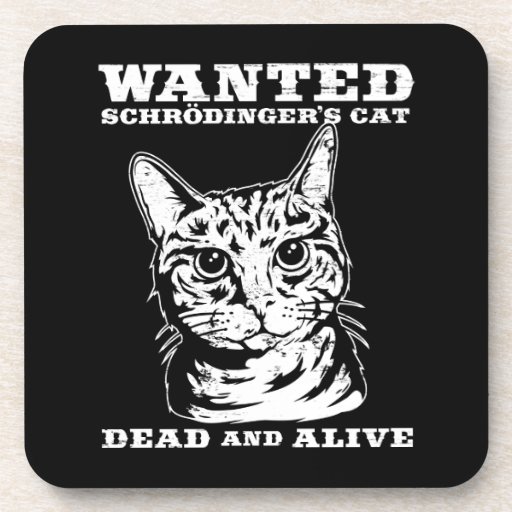

![The Virtual Self @nora3000 at #Brocku [visual notes]](https://farm9.staticflickr.com/8097/8579185198_ff7557417f_c.jpg)

- The Virtual Self, visual notes by Giulia Forsythe on a talk by Nora Young at Brock University March 2013 (Learn more about Giulia’s amazing Visual Practice here).

It has been a treat to delve deeper into the web of scholarship that charts the intersection of so many different philosophical inquiries that concern pedagogy as a branch of the digital humanities these last few weeks. The metaphysical and epistemic questions that guide our social, ethical and political discussions around the larger purposes of curriculum cast an incredibly broad net, but are undeniably arising out of the digital revolution in communicative technology we are living through. And so my bibliography covers a lot of ground:

- What is knowledge in the digital age? How is it attained, where does it ‘live’?

- If in fact knowledge has changed, how should we go about teaching in this new era?

- And how do these shifts in knowledge and social processes affect the nature and purpose of citizenship?

Answers to these questions lie in fields of sociology, philosophy, political science, and education, but I have tried to locate and share readings that plot the intersection of these topics as relates the narrower field of ‘curriculum.’

Andreotti, V. d. O. (2011). The political economy of global citizenship education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9(3-4), 307-310.

Biesta, G. (2013). Learning in public places: Civic learning for the 21st century. Civic learning, democratic citizenship and the public sphere.

Biesta, G. J. J. (2012). Doing Emancipation Differently: Transgression, Equality and the Politics of Learning. Civitas Educationis. Education, Politics and Culutre, 1(1), 15-30.

Downes, S. (2012). Connectivism and connective knowledge: Essays on meaning and learning networks. National Research Council Canada, http://www. downes. ca/files/books/Connective_Knowledge-19May2012. pdf.

Feldman, S. B., & Tyson, K. (2014). Clarifying Conceptual Foundations for Social Justice in Education International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Social (In) Justice (pp. 1105-1124): Springer.

Garcia, J., & De Lissovoy, N. (2013). Doing School Time: The Hidden Curriculum Goes to Prison. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 11(4).

Howard, P. (2014). LEARNING COMMUNITIES AND DIGITAL CITIZENSHIP IN ONLINE AFFINITY SPACES: THE PROMISE AND THE PERIL. INTED2014 Proceedings, 5658-5658.

Khoo, S.-m. (2013). Between Engagement and Citizenship Engaged Scholarship (pp. 21-42): Springer.

Lentz, B. (2014). The Media Policy Tower of Babble: A Case for “Policy Literacy Pedagogy”. Critical Studies in Media Communication(ahead-of-print), 1-7.

MacGregor, J., Stranack, K., & Willinsky, J. (2014). The Public Knowledge Project: Open Source Tools for Open Access to Scholarly Communication Opening Science (pp. 165-175): Springer International Publishing.

Martin, C. (2011). Philosophy of Education in the Public Sphere: The Case of “Relevance”. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 30(6), 615-629.

Monteiro, H., & Ferreira, P. D. (2011). Unpolite Citizenship: The Non-Place of Conflict in Political Education. JSSE-Journal of Social Science Education, 10(4).

Queen, G., Ross, E. W., Gibson, R., & Vinson, K. D. (2013). I Participate, You Participate, We Participate…”: Notes on Building a K-16 Movement for Democracy and Social Justice. Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor(10).

Rice, J. (2013). Occupying the Digital Humanities. College English, 75(4), 360-378.

Schugurensky, D., & Silver, M. (2013). Social pedagogy: historical traditions and transnational connections. education policy analysis archives, 21, 35.

Sidorkin, A. M. (2010). John Dewey: A Case of Educational Utopianism. Philosophy of Education Archive, 191-199.

Sidorkin, A. M. (2014). On the theoretical limits of education Making a Difference in Theory: Routledge.

Siemens, G. (2014). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age.

Talisse, R. B. (2013). Sustaining democracy: folk epistemology and social conflict. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 16(4), 500-519.

Willinsky, J. (2013). Teaching for a World of Increasing Access to Knowledge. CALJ Journal, 1(1).