“The average time spent with screen media among 8- to 18-year-olds is more than twice the average amount of time spent in school each year.” (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010; National Center for Education Statistics, 2007–2008)

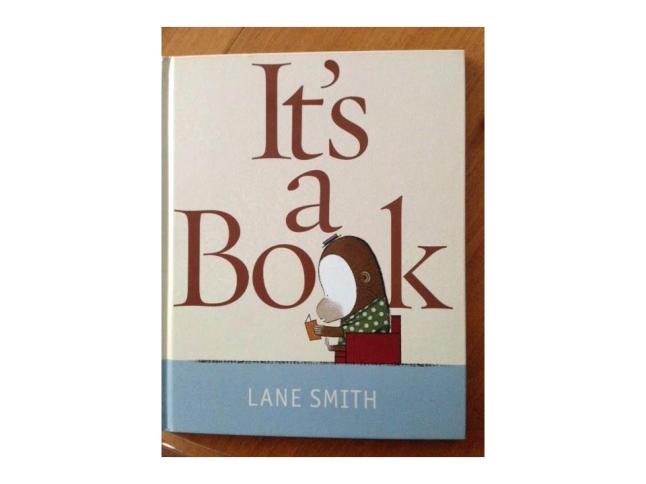

Whenever I think about use of technology in the classroom and its impact on learning and attention, I cannot help but make connections to the book, “It’s a Book” by Lane Smith. The book centers on two characters. One is a digital native and the other is an analogue learner. The two of them are having different experiences with a paper book. When I read it I think of the analogue learner as a grandfather and digital native as a grandson.

- CAN IT TEXT?

- BLOG?

- SCROLL?

- WI-FI?

- TWEET?

- No… it’s a book.

We live in a vastly different technological world than we did just 10 years ago, and advances in technology are unlikely to slow down. Realistically, these advances are likely to tax our attention more and more. We no longer need to ask the question Do advances in technology affect our learner’s attention? Because there is mounting evidence to support this. In a recent New York Times article titled Technology Changing How Students Learn, Teachers Say Dr. Christakis showed that students saturated by entertainment media, experience “supernatural” stimulation that teachers might have to keep up with or simulate. He further explained that heavy technology use “Makes reality by comparison uninteresting.” Daniel Goleman, author of Emotional Intelligence, claims there exists the possibility physiological changes in the brain as a result of advances in technology, “Children I’m particularly worried about because the brain is the last organ of the body to become anatomically mature. It keeps growing until the mid-20s,”

The question we need ask ourselves as educators is “How do we continue to provide engaging and meaningful learning experiences for students with or without attention difficulties? Research conducted with the help of classroom teachers by Common Sense Media, a non-profit organization that studies the effects that media and technology have on young users, shows that technology advances have affected learner’s ability to attend to a variety of tasks, but at the same time the research found an increase in learner’s ability to find new information and multitask effectively. A recent Psychology Today article written by Jim Taylor, Ph.D. supports some of the findings in the Common Sense Media research by claiming that exposure to technology isn’t all bad.

“Research shows that, for example, video games and other screen media improve visual-spatial capabilities, increase attentional ability, reaction times, and the capacity to identify details among clutter. Also, rather than making children stupid, it may just be making them different.”

I think it is safe to say that in order to develop successful learners who are able to contribute meaningfully to society a balance needs to be established with the use of technology.

Attention In My Grade 5/6 Classroom

I have worked in the same grade 5-6 classroom for the last five years, and the majority of my students spend many hours interacting with technology by playing video games and watching YouTube videos. It is difficult to establish whether there is a direct link between increased in screen time and a drop in learner’s ability to attend tasks, but what is clear is the difficulty I have in capturing and maintain attention in class. It would be pompous of me to think I do not own a slice of the problem, and need to continue to work on improving my learning design to better suit the needs of my learners, but I work in a system that is slow to change and adapt to a different style of learner.

So How Do We Adapt To Attention Changes Within Our Learners?

-

We can use stories to capture and hold learner’s attention. Stories are logical, they have a sequence we are all familiar with, they promote questioning and inferring, and can create and convey strong emotions.

-

Use visuals cues such as infographics to help students absorb information. “Verbal and visual cues are processed differently by the brain….Unless someone has a vision or related impairment, they learn from visuals.” Dirksen

-

Allow students to work in groups. Group work creates a space for positive social interactions, support, and leadership.

-

Ask questions that cannot be answered by a simple Google search. Ask questions that require learners to interpret

-

Put your students a state of cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance occurs when learners are present with an event that is contradictory to their own experiences.